Concrete in Practice Part I: Organization

It is sometimes said that we can never really understand an industry until we see it from the inside. This is an industrialized version of “If you want to understand someone, walk a mile in their shoes.” If this is true, it is perhaps most true of construction. We have all driven by projects, wound our way through construction zones and witnessed the end results.

It is sometimes said that we can never really understand an industry until we see it from the inside. This is an industrialized version of “If you want to understand someone, walk a mile in their shoes.” If this is true, it is perhaps most true of construction. We have all driven by projects, wound our way through construction zones and witnessed the end results.

If dollar value is any indication, construction’s economic impact on a nation’s prosperity is clear and unequivocal. Between 1975 and 1995, the construction industry was responsible for between 7%-9% of US Gross Domestic Product (GDP: the market value of all goods and services produced in America). According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, average wages for construction workers rose from $3.41-per-hour in 1966 to $20.02-per-hour in 2006 (a rise of 82.9% over four decades). Here is the ultimate dollar value of all that work:

Construction has historically been viewed as the “bricks-and-mortar” of economic growth. Naturally, the industry is structured almost as its own society; managers, workers, contractors, subcontractors – all role players vested in the final result.

We know what they contribute, but how many of us know what builders really do (aside from the obvious)? We can see the phases of a project as a logical sequence, but each and every one requires coordination. Construction project are a logistic world based on time and communication.

Project managers have historically been viewed as the totems of responsibility for the success of construction projects. After all, they manage it all. From turning sod to turning over the keys, managers coordinate workers. Project managers have a broad skill set, but communication is one of the most influential of them. In fact, communication is the crucial link that bonds all parties in the ongoing dialogue that is construction. When communication breaks down, the project may follow. It may not happen right away, it may not happen at all. However, construction projects become management risks when the need to communicate is replaced by silence.

The Squeaky Wheel

The bigger the project, the more important is communication. This is because projects employ more direct workers and subcontract more work than do many other industries. One person appears to put in the pipes, another one wires the walls. Another contractor installs the closets. When subcontractors deliver as directed, trades people engage to  deliver their result to general project managers (sometimes referred to as general contractors). GMs report to Project Managers. They report to owners. A successful construction project can be defined by each team player’s ability to not only deliver the work, but to communicate effectively about its progress. From top to bottom, that is how all construction projects are navigated to their targeted completions.

deliver their result to general project managers (sometimes referred to as general contractors). GMs report to Project Managers. They report to owners. A successful construction project can be defined by each team player’s ability to not only deliver the work, but to communicate effectively about its progress. From top to bottom, that is how all construction projects are navigated to their targeted completions.

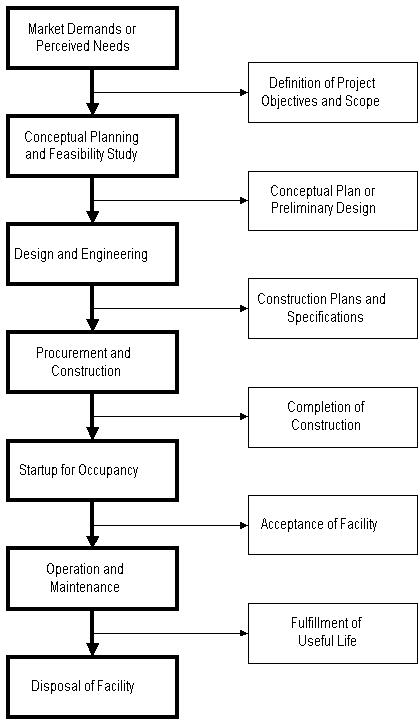

A construction project’s “Life Cycle”(pictured here) is the mammoth step-by-step process which most often begins with either a desire or a need (sometimes both simultaneously). From there, the grand design flows from the thought to the structure over time.

The minute we introduce humanity into a structural equation, we introduce human flaw. That’s the bad news. The good news is that humans also manufacture ways to detect their own mistakes. In construction, there is one device which pre-empts problems before they even occur. Discover what it is in the conclusion to “Concrete in Practice.”

Sources:

Hendrickson, Chris and Tung Au “Chapter 1: The Owners’ Perspective.” Project Management for Construction: Fundamental Concepts for Owners, Engineers, Architects and Builders. 1st Edition. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1989.

Hendrickson, Chris Project Management for Construction: Fundamental Concepts for Owners, Engineers, Architects and Builders. Pittsburgh, PA: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University; Version 2.2, Summer 2008.

Table B-2: Average Hours and Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees on Private Nonfarm Payrolls by Major Industry Sector (1966-to-Date). Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.